Tariff, Trade, and Addiction: the 1903 US-Sino Treaty

How a Century-Old Treaty Between the U.S. and China Addressed Drugs, Trade, and Sovereignty

Today, President-elect Donald Trump announced plans to impose new tariffs—20% on Canada and Mexico and 10% on China—on his first day in office in response to drug imports and illegal immigration. The move reminded me of a historical episode in which trade policy and drug trade were similarly intertwined in US-China relations. I hoped to write a longer post on the topic someday, but given my current schedule and today’s news, I decided to introduce the event briefly first.

At the turn of the 20th century, China, reeling from the devastation of the Boxer Rebellion and the humiliation of unequal treaties, was under immense pressure to modernize its systems while trying to regain sovereignty. The U.S., relatively new to the Western power club, saw an opportunity to cement its influence.

While Britain and France dominated Chinese trade through their control of treaty ports and customs revenues, and Japan was emerging as a military force in the region, the U.S. sought a subtler strategy. It pursued commercial expansion under the banner of the Open Door Policy, which called for equal access to Chinese markets for all foreign nations. This policy ostensibly promoted free trade but also sought to prevent any single nation from dominating China entirely.

Against this backdrop, diplomats from the U.S. and China convened in Shanghai in October 1903 to sign a treaty. The treaty’s main provisions included opening more ports to trade, reforming internal tariffs, and addressing opium addiction in China.

“The signing of a new commercial treaty with China, which took place at Shanghai on the 8th of October, is a cause for satisfaction. This act, the result of long discussion and negotiation, places our commercial relations with the great Oriental Empire on a more satisfactory footing than they have ever heretofore enjoyed. It provides not only for the ordinary rights and privileges of diplomatic and consular officers, but also for an important extension of our commerce by increased facility of access to Chinese ports, and for the relief of trade by the removal of some of the obstacles which have embarrassed it in the past.”

—Annual Message to Congress, President Theodore Roosevelt, December 9, 1903 (Source: https://teachingamericanhistory.org/document/state-of-the-union-address-99/)

A significant part of the treaty was the abolition of the likin tax. This internal transit toll, levied on goods moving through China, provided much-needed revenue to mitigate the Qing Dynasty’s fiscal crises. However, both Chinese merchants and foreign traders despised the tax for its inefficiency and corruption. For foreign powers like the U.S., the likin tax was seen as an impediment to free trade.

However, abolishing the likin tax posed a challenge: how would the Qing government replace this crucial source of revenue? The treaty addressed this by allowing China to impose a surtax on imports and exports (for example, a surtax up to 1.5 times the import duty). This surtax gave China potentially a more stable and centralized revenue stream, with the caveat that tariff revenue was managed by the Imperial Maritime Customs Service, a semi-foreign-operated agency. In the meantime, eliminating the likin tax gave the U.S. and other foreign powers the predictability they craved in trade.

In the treaty, China also committed to protecting U.S. citizens' trademarks, patents, and copyrights, issuing protections, and enforcing them under newly established laws and offices. The U.S. agreed to support China’s efforts to modernize its judicial system, with the possibility of relinquishing extraterritorial rights if reforms met international standards.

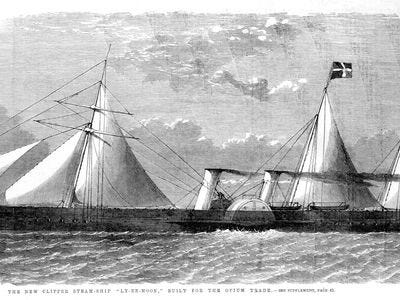

Notably, the treaty also tackled the opium trade. By the time the treaty was signed, opium had devastated Chinese society for generations. The two Opium Wars (1839–1842 and 1856–1860) forced China to legalize the trade and cede control over its own ports to foreign powers.

In the 1903 treaty, the U.S. reaffirmed its ban on American participation in the opium trade, signaling a moral high ground compared to Britain, which had profited handsomely from opium sales. Additionally, the treaty imposed restrictions on the importation of morphine, the refined derivative of opium, except for strictly regulated medical purposes.

In doing so, the U.S. offered cooperation as China sought to curb the spread of what we might call the 19th century’s version of fentanyl. By cooperating with China on opium restrictions, the U.S. reinforced its image as a cooperative partner, which helped advance its Open Door Policy and ensure U.S. merchants gained equal access to Chinese markets.

Was the treaty effective from China’s perspective? It was signed under duress in a context where China’s sovereignty was heavily compromised. The broader constraints of the unequal treaty system limited China's benefits. The process of crafting a modern legal system—including its first intellectual property laws—was slow and fraught with conflicting interests between the West and Japan and both domestic and foreign resistance. As for opium, the treaty did little to curb its imports, as enforcement was weak and American influence over the opium trade was limited.

Yet, the treaty represented a step toward. Abolishing the likin tax was a move toward liberalizing the Chinese market. China’s determination to regain sovereignty led to the push to modernize legal systems. The two countries’ agreement to restrict the opium trade hinted at the possibility of greater international responsibility.

Of course, the dynamics between the U.S. and China are vastly different and, in some ways, reversed today. China is no longer a weakened empire but a global superpower. The U.S. now grapples with a devastating opioid epidemic and is considering imposing tariffs on its largest trading partners. However, the 1903 US-Sino Treaty shows that trade policy has rarely been just about trade and, throughout history, intersected with issues far beyond, including epidemics.