This week, tariffs are back in the spotlight, with the U.S. set to hike duties on imports from familiar names: China, Canada, and Mexico. Supporters of these policies often point to the late 19th century as a golden era when high tariffs supposedly fueled America’s industrial dominance. But peel back the layers of American history, and you’ll find a far messier reality behind the enduring debates over tariffs, from Alexander Hamilton’s carefully balanced proposals for nurturing infant industries to the economically disastrous Smoot–Hawley debacle.

Even before the ink dried on the Constitution, trade was a battleground. John Jay’s dream of unimpeded commerce reflected the Founding generation’s unease with Britain’s habit of manipulating its colonies’ trading patterns through political interventions, but clashed with the economic realities of a young nation struggling for stability.

The nation’s first tariff law, proposed by James Madison in 1789, sought to impose modest import duties to fund government operations. It was, however, quickly hijacked by factions demanding protection for domestic manufacturers. Madison himself warned of the risks of excessive duties, predicting the factionalism and rent-seeking that would come to define U.S. tariff policy.

Alexander Hamilton later laid out his case for strategic protectionism. His Report on Manufactures remains a touchstone for tariff defenders today, but even Hamilton advocated moderation, emphasizing the importance of balancing revenue needs with limited protectionist measures.

Fast forward to the 19th century, which turned out to be a rollercoaster of tariff policy, swinging between protectionism and free trade depending on who held the reins in Washington. The post-War of 1812 boom and Henry Clay’s “American System” showed what high tariffs could do—but also how divisive they could be. Henry Clay championed the American System, a policy agenda combining high tariffs, infrastructure investment, and a national bank to promote economic self-sufficiency. Clay’s proposals met opponents like James Madison and Thomas Jefferson, who argued that such measures exceeded constitutional limits.

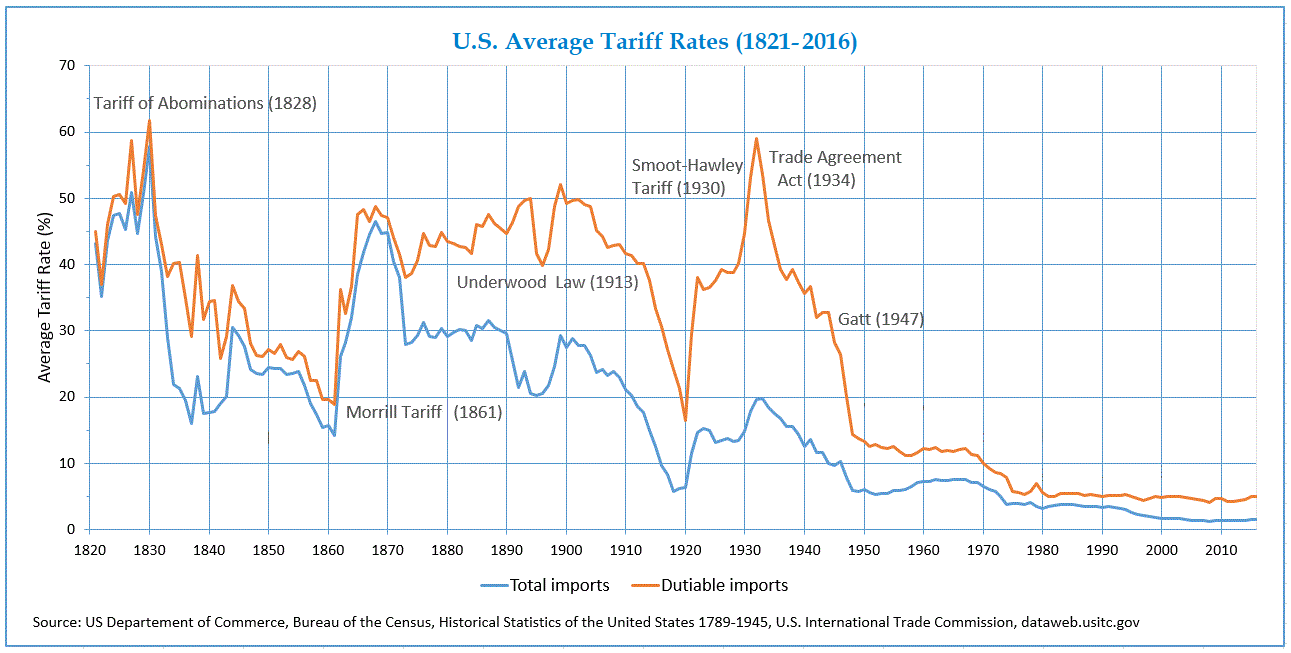

The “Tariff of Abominations” in 1828 raised rates to over 60%, provoking outrage in the South, where agricultural exporters bore the brunt of retaliatory measures. This crisis culminated in the Compromise Tariff of 1833, which reduced rates over time to alleviate sectional tensions. The Walker Tariff of 1846 marked a significant shift toward free trade, aligning with Britain’s repeal of the Corn Laws and fostering a period of relatively open commerce.

The Civil War brought a return to protectionism, with the Morrill Tariff of 1861 raising rates significantly to fund the Union war effort. Supported by industrial interests in the North, high tariffs persisted through the late 19th century. This period marked the start of an era of high tariffs that coincided with America’s rise to economic prominence.

But correlation isn’t causation—a point highlighted by Doug Irwin’s work on the 1807-1814 trade embargo and the Morrill Tariff era. Irwin uses disaggregated data on U.S. industrial production and finds that the trade disruptions did not accelerate U.S. industrialization. Instead, the disruptions may have shifted resources from trade-dependent industries (such as shipbuilding) to domestic infant industries (such as cotton textiles). On the Morrill tariffs, Irwin shows that America’s rapid growth in the late 19th century stemmed more from population expansion and capital investment than productivity boost from tariff protections. In fact, tariffs may have discouraged capital accumulation by raising the price of imported capital goods. Irwin also finds that productivity growth was most rapid in non-traded sectors (such as utilities and services), whose growth was not attributed to tariffs but ultimately helped the U.S. overtake the U.K. in GDP per capita.

Fast forward to the 20th century, which drove home the pitfalls of protectionism. In the first decades of the 1900s, the U.S. doubled down on its high-tariff policies except for a brief shift in the early 1910s. The Underwood-Simmons Tariff of 1913 lowered tariffs significantly and introduced an income tax. This shift was, however, short-lived. During the 1928 election campaign, Herbert Hoover pledged to help farmers by raising tariffs on agricultural products. Once the tariff revision process started, it became impossible to stop. Calls for increased trade protection flooded in from all sectors. Congress ultimately enacted the Tariff Act of 1930, also known as the Smoot-Hawley tariff, raising average tariff rates to nearly 60%. Instead of shielding American industries during the Great Depression, the Act triggered a global trade war and worsened the economic crisis. Exports collapsed, and the economic malaise deepened.

Recognizing the need for reform, the Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act (RTAA) of 1934 shifted tariff-setting authority to the executive branch, enabling bilateral trade agreements. This paved the way for post-World War II trade liberalization under frameworks like the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT).

In our next post, we will look at how the U.S. trade policy evolved after GATT, navigating the tug-of-war between free trade ambitions and protectionist pressures—a journey that ultimately led to a full-blown trade war. While history warns us of the costs of tariffs, from higher consumer prices to stifled innovation, the siren song of tariffs—promising quick fixes and national pride—remains as seductive as ever.

Continue reading: Part II - U.S. Trade Policy from GATT to Trade Wars