Starting this week, chances are, if you live in the U.S., most of what you buy—whether it’s a car, a computer, or even a chicken sandwich—is affected by tariffs. Tariffs are soon everywhere, altering the prices of goods, the strategies of U.S. and non-U.S. firms, and long-existing value chains in North America and around the world.

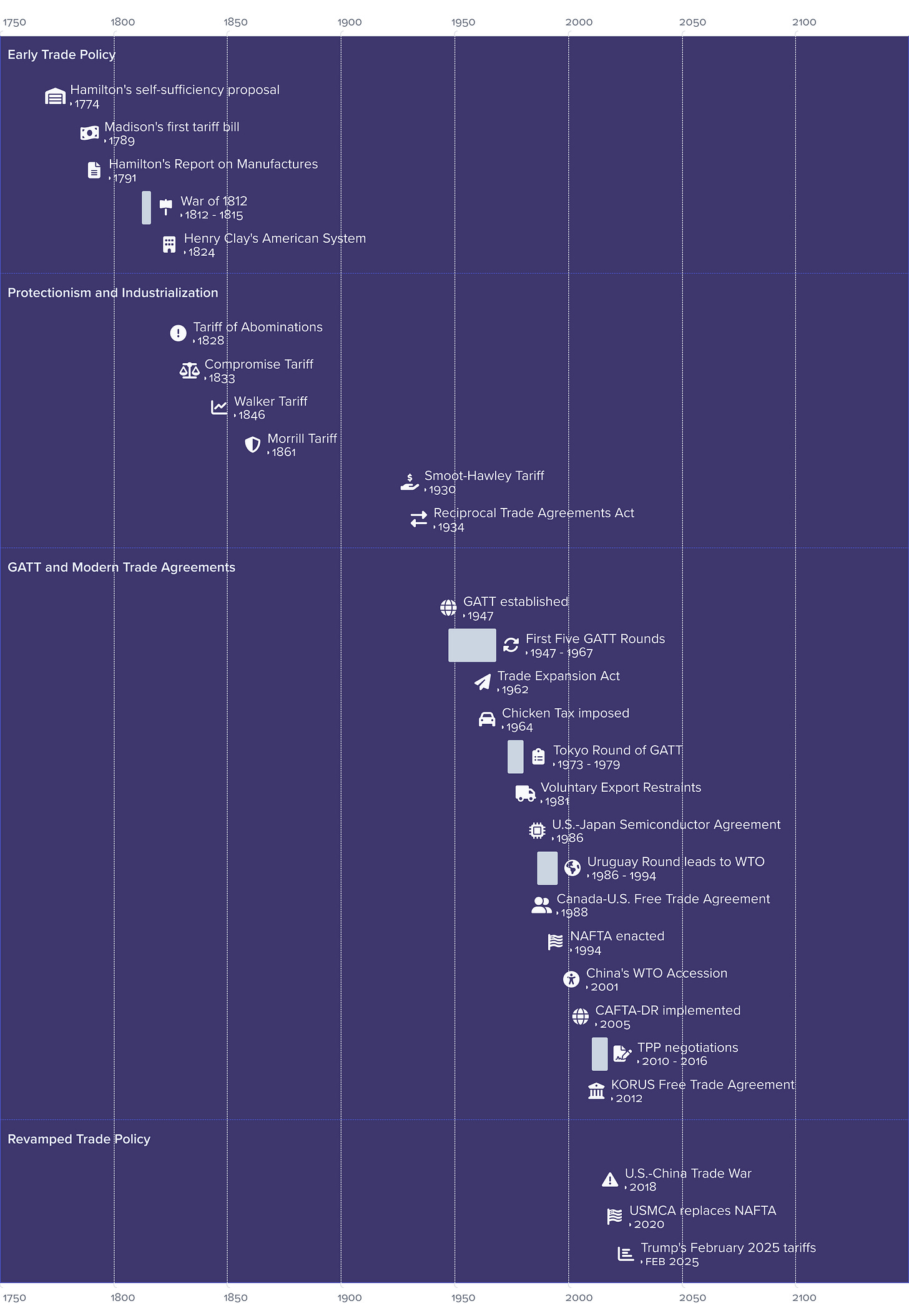

In our previous post “A Quick Look Back at America's Historical Tariffs”, we explored the history of U.S. tariffs before the establishment of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) in 1947. Today, we continue the story, looking at how U.S. trade policy has swung between two conflicting forces in the following decades: the push for free markets and the protection of American industries. We will also see how the story can sometimes get just plain weird—like how Ford shipped its Transit Connect vans from Turkey with fake seats and windows, only to rip them out upon arrival in the U.S., all thanks to a decades-old trade dispute with the EU over chicken. While the legal battle ended in March 2024 with Ford agreeing to pay $365 million, we may see similar stories emerging soon.

The Post-War Push for Free Trade (1944–1960s)

At the end of World War II, the global economy was in ruins. Countries needed a way to rebuild, and economic cooperation became a key priority. At the Bretton Woods Conference in 1944, the U.S. led efforts to create a new international financial system, which included not only the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank but also a framework for lowering trade barriers.

This push culminated in the establishment of GATT in 1947, a landmark agreement aimed at reducing tariffs and fostering global trade. Through multiple rounds of negotiations, tariffs on industrial goods were slashed, dropping from an average of over 30% in 1944 to around 12% by the 1960s. President John F. Kennedy’s Trade Expansion Act of 1962 took things further, giving the White House the power to cut tariffs by up to 50%.

At the time, free trade was widely celebrated. The U.S. was the world’s manufacturing powerhouse, and American companies thrived in global markets. However, not everyone was on board. Agriculture remained largely protected, ensuring U.S. farmers weren’t undercut by foreign competition. The textile and apparel industries fought fiercely to maintain tariffs and quotas, and the automobile industry began to worry that foreign competition could eventually threaten its dominance.

The Rise of Trade Disputes (1970s–1990s)

By the 1970s, things started to shift. Japan and Europe were no longer war-ravaged economies rebuilding from scratch and emerged as formidable industrial competitors. Suddenly, American steelmakers, automakers, and textile manufacturers weren’t just competing with each other; they were competing with highly efficient foreign producers.

Rather than reintroducing broad tariffs, the U.S. turned to a different strategy: Voluntary Export Restraints (VERs). These were agreements in which foreign producers voluntarily limited their exports to the U.S. to avoid more severe trade restrictions. One of the most famous examples was the 1981 agreement with Japan, which capped Japanese auto exports in an effort to protect Detroit’s Big Three automakers.

Yet, even as protectionist pressures mounted, trade liberalization continued. The Tokyo Round (1973–1979) of GATT further reduced tariffs, and the Uruguay Round (1986–1994) paved the way for the creation of the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 1995. The biggest trade agreement of the decade, however, was NAFTA (1994), which eliminated most tariffs between the U.S., Canada, and Mexico by 2008.

At the same time, industries continued to seek protection. The textile sector fought to keep the Multi-Fibre Arrangement (MFA) in place, ensuring that foreign imports remained capped. The steel industry lobbied aggressively for anti-dumping tariffs, arguing that foreign producers were unfairly selling steel below market prices.

And then there was the Chicken Tax—a tariff that had nothing to do with steel or cars yet shaped the American auto industry for decades.

The Chicken Tax: A Tariff That Outlived Its Purpose

In the early 1960s, the U.S. found itself in a trade war over an unexpected commodity: chicken. European nations, led by West Germany, imposed tariffs on American poultry, claiming it was unfairly priced. The U.S. government, determined to retaliate, didn’t slap tariffs on chicken exports—but instead targeted imported light trucks and commercial vans.

Thus, the Chicken Tax of 1964 was born. A 25% tariff on imported light trucks was introduced, with Volkswagen’s Type 2 vans as the primary target. While the poultry dispute was eventually resolved, the tariff never went away.

Fast forward to the 21st century, and the Chicken Tax was still distorting the auto industry. Foreign automakers largely avoided selling small trucks in the U.S., choosing instead to build factories domestically—or resort to creative loopholes.

Take Ford’s Transit Connect vans, for example. Built in Turkey, they should have been subject to the 25% Chicken Tax. But according to a DOJ investigation, Ford found a workaround: the company shipped the vans with seats and rear windows, classifying them as passenger vehicles, which were only subject to a 2.5% tariff. Once they arrived in the U.S., Ford ripped out the seats and windows before selling them as commercial vans.

The government ultimately cracked down on this practice, and in March 2024, Ford settled the case for $365 million. But the Chicken Tax remains in place today, proving just how difficult it is to repeal a tariff once it takes hold.

The WTO Era and China’s Rise (1995–2016)

By the late 1990s, free trade seemed unstoppable. The WTO was established in 1995, providing new enforcement and dispute settlement mechanisms for global trade rules. At the same time, NAFTA was creating an integrated North American market, allowing U.S. companies to move production to Mexico while still benefiting from tariff-free exports.

But the biggest shift came in 2001, when China joined the WTO. The U.S. granted Permanent Normal Trade Relations (PNTR) status to China, ushering in a flood of Chinese imports, particularly in electronics, textiles, and steel.

The impact was profound. On one hand, American consumers enjoyed lower prices on everything from clothing to home appliances. On the other hand, many manufacturing industries struggled to compete. The U.S. trade deficit with China exploded, and manufacturing jobs vanished, a phenomenon termed the “China Shock” by economists such as David Autor.

Notably, nearly all analyses show that U.S. aggregate gains from trade with China are positive. And trade, including trade with China, Canada, Mexico, and more, created new opportunities. In agriculture, for example, American soybean and corn producers found a lucrative market in China. U.S. agricultural exports surged, making China one of the biggest buyers of American farm goods. Silicon Valley boomed, tech jobs grew, and the U.S. remained a leader in services and finance. But all of that wasn’t much consolation to the factory workers in Ohio or Michigan.

By the mid-2010s, the U.S. was no longer just fighting to protect its factories—it was battling for its place as the world’s dominant economic force. The government ramped up anti-dumping duties, countervailing tariffs, and Section 301 investigations, not just to shield American industries but to challenge China’s growing economic power. At the same time, the trade battleground shifted from assembly lines to algorithms, from steel mills to semiconductor fabs. The future wasn’t just about who could produce the cheapest goods; it was about who would control the most valuable technologies.

NAFTA Replacement, TPP, and Trade War (2016-)

By the late 2010s, NAFTA had also become a political lightning rod. While it had significantly increased trade between the U.S., Canada, and Mexico, critics—especially in the U.S.—argued that it had contributed to outsourcing and job losses in key manufacturing sectors. The Trump administration seized on this discontent, renegotiating NAFTA and replacing it with the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) in 2020.

USMCA kept much of NAFTA intact but introduced new rules aimed at benefiting American workers. It required higher domestic content in automobiles, meaning that 75% of car parts had to be sourced from North America (up from 62.5% under NAFTA). It also included stronger labor protections, compelling Mexico to strengthen workers' rights to prevent unfair labor competition. While it was hailed as a win for American workers and manufacturers, many economists saw it as a modernization rather than a true overhaul of NAFTA.

While the Trump administration was renegotiating NAFTA, it was also withdrawing the U.S. from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP)—a major trade deal negotiated during the Obama administration. The TPP aimed to create a massive free-trade bloc covering 12 Pacific Rim nations, including Japan, Australia, Canada, and Mexico. It was designed not just as a trade deal but as a geopolitical counterweight to China, which was notably absent from the agreement.

However, in 2017, Trump pulled the U.S. out of TPP, arguing that it would harm American workers. Without the U.S., the remaining 11 countries moved forward, signing a revised version called the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP). Many experts view the U.S. withdrawal as a missed opportunity, as it left an opening for China’s Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) to become the dominant trade pact in Asia.

The escalating great-power rivalry, fueled by rising nationalist sentiment, also erupted into the largest trade war of the 21st century—one that began in 2016 and still rages on. And now, it’s taking another dramatic turn. The new 25% tariffs on Canada and Mexico and a fresh 10% tax on Chinese imports on the grounds of economic security, immigration control, and a crackdown on illicit drug flows could reshape North American and global supply chains for the long run.

We’ve seen this before (for example, tariffs and opioid epidemics were already intertwined in U.S.-China trade relations over 100 years ago). Tariffs are never just about economics—they are about power, leverage, and control. And whether it’s cars, steel, soybeans, or even chicken, trade wars have a way of spilling into every aspect of our lives.

So, buckle up. The next chapter of America’s tariffs has just begun. And no matter where you stand, we are all in this together.