“I almost went down on my knees to beg him to veto it.”

— Thomas Lamont, J.P. Morgan & Co., on pleading with President Hoover

Back in January, we took a quick look at the history of U.S. tariffs from early protectionist roots to 20th-century trade reform. Today, we’re diving into one of its most infamous chapters: the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act.

Born out of political pressure and economic anxiety, the bill arrived in the midst of a global slowdown and left behind a wreckage of collapsed trade, fractured alliances, and a deepened depression.

This is how the tariff bill shrank the global economy.

The Origin

By the late 1920s, rural America was in trouble. Wheat prices had crashed. Tractors and mechanization had boosted productivity, but also laid off workers. The land was producing more than the market wanted. Rural banks were failing, and auctions of foreclosed farms became grim community rituals.

When Herbert Hoover ran for president in 1928, he promised help. Specifically, he pledged to raise tariffs on imported farm goods to shelter American farmers from cheaper competition. Congress responded with a bill focused on just that.

But the tariff train didn’t stop at wheat and wool.

Once the legislative process began, lobbyists flooded Washington as we had seen before for the nation’s first tariff law by James Madison. Manufacturers demanded protection for everything from textiles to ball bearings.

The House passed the tariff hike easily in 1929. The Senate was more contentious. It took months of what observers called “logrolling” — trading votes like baseball cards — to get it through. The result? A sprawling, bloated bill that raised tariffs on over 20,000 imported products.

Behind closed doors, President Hoover was alarmed. He privately called the bill “vicious, extortionate, and obnoxious.” But political pressure mounted. His own party backed it. Industrial donors supported it. And with the economy already shaky after the 1929 stock market crash, Hoover hesitated to appear inactive.

On June 17, 1930, he signed the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act into law.

The Protests

The backlash was immediate and global.

“An economic stupidity.” — Henry Ford

“Asinine.” — Thomas Lamont, J.P. Morgan

“This will deepen the depression.” — 1,028 economists, in an open letter to Hoover

Even before the act was law, 23 countries lodged formal diplomatic protests. Canada, America’s closest trade partner at the time, was furious. In May 1930, within days of Hoover’s signature, Canada retaliated, imposing new tariffs on 16 U.S. products — affecting over 30% of American exports to Canada.

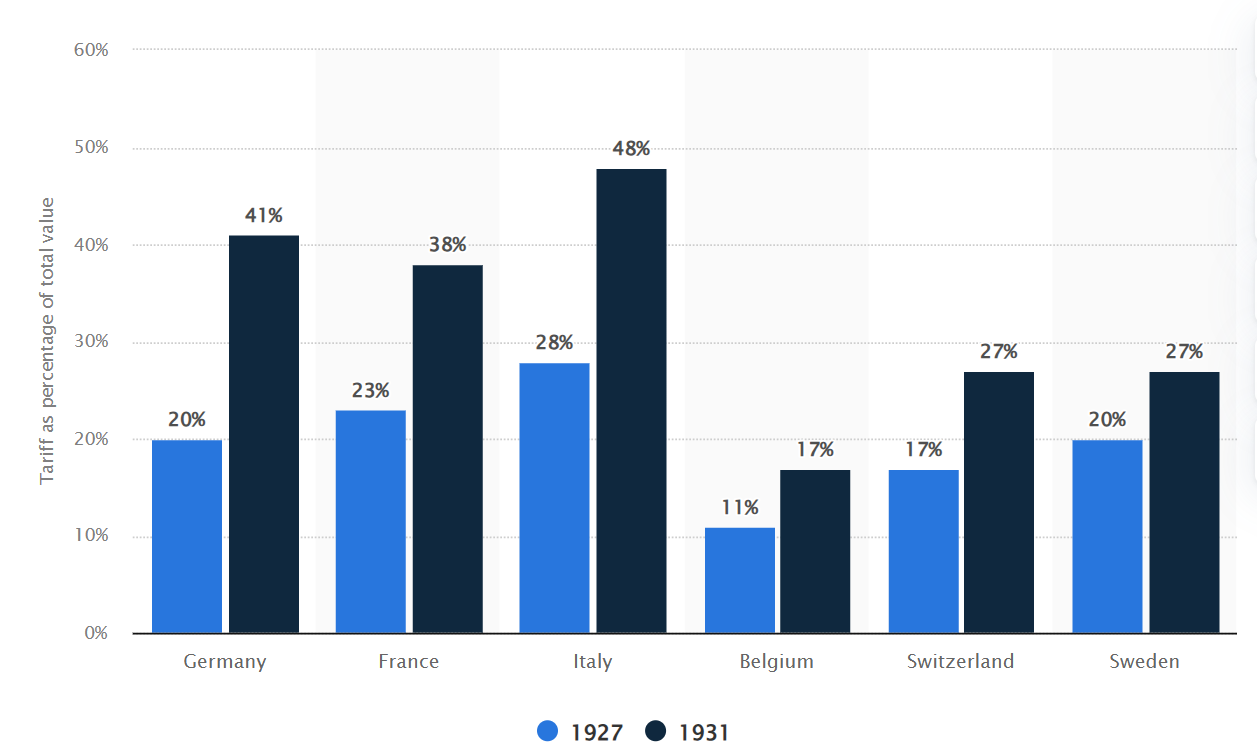

And Canada wasn’t alone. Britain, France, Italy, Mexico, Cuba, Spain, and over 25 others followed with retaliatory tariffs or trade preferences that shut the door on U.S. exports. Germany, for example, doubled the average tariff rate from 20% to 41% by 1931. France similarly raised tariff rates by 15 percentage points on average.

A global trade war soon erupted, driven not by ideology, but by a chain reaction of short-sighted self-interest.

The Collapse

Within two years of Smoot-Hawley, the volume of U.S. imports plunged by over 40%. By 1933, amid worldwide depression and tariff retaliation, U.S. imports had fallen 66% in value. At the same time, U.S. exports also fell sharply by about 61%.

World trade as a whole went into freefall: by 1933, global trade was roughly one-third of its 1929 level, a stunning two-thirds decline over four years. While the Great Depression itself (with collapsing demand and prices) accounts for much of this contraction, Smoot-Hawley’s high tariffs exacerbated the collapse in international commerce.

The tariff hike did little to “protect” the overall U.S. economy; instead, key indicators deteriorated in its wake. The U.S. GNP fell from $103 billion in 1929 to $76 billion in 1931, bottoming out at $56 billion by 1933. This represents an extraordinary contraction of nearly 46% in nominal GNP over four years.

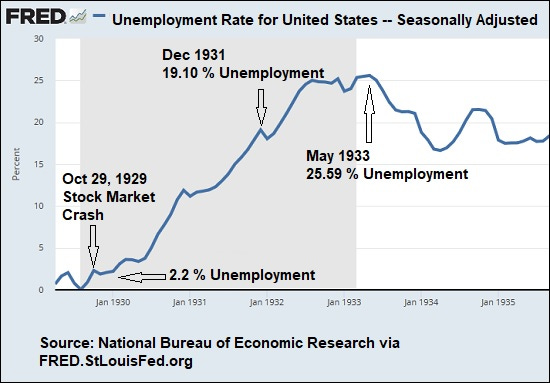

Industrial production also plummeted by roughly 50% from 1929 to 1932 as demand evaporated. Unemployment, around 3% in 1929, had already risen to about 8–9% by 1930 as the Depression began. After the Act, it skyrocketed: joblessness hit 16% in 1931 and reached about 25% – roughly 12 million Americans – by 1932–33. One in four Americans was unemployed. It wasn’t all Smoot-Hawley’s fault, but the act became a multiplier for economic despair.

In short, the early 1930s saw the U.S. economy collapse on multiple fronts: output, prices, and employment all fell drastically, and the hoped-for benefits of import protection (such as increased domestic production or jobs) failed to materialize.

Even sectors ostensibly “protected” by the tariff suffered as overall demand and credit dried up. For example, U.S. farmers faced continued hardship: export markets for agricultural goods shrank due to foreign retaliation and falling incomes, contributing to hundreds of bank failures in rural areas.

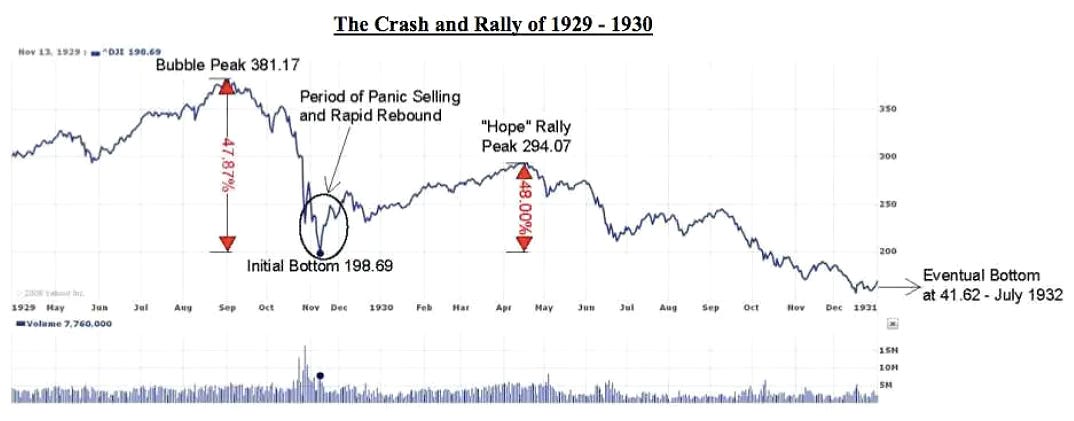

The economic turmoil was also reflected in the dramatic collapse of the U.S. stock market, from the peak in late 1929 through the deep bottom of 1932. The market hit a high of 381.17 in November 1929 before plummeting nearly 48% to an initial low of 198.69 following the infamous crash. A brief "hope rally" in early 1930 brought the index back to 294.07, but this recovery was short-lived. Over the next two years, the market steadily declined, eventually bottoming out at 41.62 in July 1932 — an almost 90% decline from its peak.

The Pivot

The political fallout was just as brutal.

Senator Reed Smoot lost re-election in 1932.

Representative Willis Hawley lost his seat the same year.

The Republican Party suffered a landslide defeat as FDR swept into office on promises of reform.

In 1934, Roosevelt pushed through the Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act (RTAA) — a direct repudiation of Smoot-Hawley. It allowed the U.S. to negotiate bilateral tariff reductions, marking a shift away from protectionism toward mutual cooperation.

From that point on, U.S. trade policy gradually liberalized. By 1947, the U.S. had joined the GATT, laying the groundwork for the postwar trading system — one designed specifically to avoid another Smoot-Hawley moment.

Today, economists and historians mostly agree: Smoot-Hawley was a disaster. Smoot-Hawley was not the beginning of the Depression, but it helped make it deeper, longer, and more global. The tariff didn't just wall off the economy; it trapped it. And it didn’t just fracture American trade; it fractured international trust.